To empathetically engage in Francis Ford Coppola's Tetro is to become almost uncomfortable in wake of the sheer nakedness with which the artist is giving himself to the audience. Coppola is creating with a reckless self-abandon, unsealing his true-life insecurities that have plagued him from childhood. It is the artist/creator ripping apart the safety of the façade that makes him appear "distinguished" to us, and then revealing the unbridled psychology that exists within every being but is hidden so that others may tolerate us. The traumas displayed in Tetro, a modern family story about a teenager who goes to Argentina to find his bohemian writer/brother, have been topical throughout Coppola's career, but previously they were always buffered by genre or the wider fictional canvas onto which he was creating a vision. The autobiographical sense in Tetro is unmistakable, as the patriarch of what is perhaps the most prominent and far-reaching family in American cinema comes clean at long last.

Not that the melodrama of this film is completely fact. But the story certainly correlates to emotional truisms deeply felt by Francis Ford Coppola, perhaps budded during those long lonely hours as a sickly polio-afflicted youth, dreaming of fame while envying and blindly loving his older brother August, the intellectual ladies' man, both boys living under the eye of a very proud and egotistical father, the composer/conductor Carmine Coppola – who may have been resentful of the eventual notoriety his children achieved. No character in Tetro is necessarily a concrete stand-in for a real-life Coppola; rather they are more possibly amalgamations of a few of them, all of the Coppolas finding multiple faces in the myriad of characters. For example, Tetro (Vincent Gallo), has changed his name, not wanting anything to do with his biological family, something that makes one think of Francis’s nephew, the movie megastar Nicolas Cage. But Tetro is also certainly August, the admired artist held in awe by his younger brother, and is also Francis. Tetro has put his talent on hold, fearful to express what he has written, while in the meantime he works in theatre as a talented lighting-man – a professional hack. Tetro’s insecurity is like Coppola's, who is admitting his frustration with his critics. His victory is to finally come forward with his creation, not caring what anyone thinks and not looking for awards. It is easy to nitpick and criticize Coppola's recent independent work for their flaws, whether here in Tetro and in 2007's Youth Without Youth, about an old man who becomes young again, much like the director’s new method. But the flaws in these two films are different from the flaws in his previous features. He just doesn't seem to care, and if he falters it is because he is playing with the reckless passion of a man who understands that he is running out of time.

Not that the melodrama of this film is completely fact. But the story certainly correlates to emotional truisms deeply felt by Francis Ford Coppola, perhaps budded during those long lonely hours as a sickly polio-afflicted youth, dreaming of fame while envying and blindly loving his older brother August, the intellectual ladies' man, both boys living under the eye of a very proud and egotistical father, the composer/conductor Carmine Coppola – who may have been resentful of the eventual notoriety his children achieved. No character in Tetro is necessarily a concrete stand-in for a real-life Coppola; rather they are more possibly amalgamations of a few of them, all of the Coppolas finding multiple faces in the myriad of characters. For example, Tetro (Vincent Gallo), has changed his name, not wanting anything to do with his biological family, something that makes one think of Francis’s nephew, the movie megastar Nicolas Cage. But Tetro is also certainly August, the admired artist held in awe by his younger brother, and is also Francis. Tetro has put his talent on hold, fearful to express what he has written, while in the meantime he works in theatre as a talented lighting-man – a professional hack. Tetro’s insecurity is like Coppola's, who is admitting his frustration with his critics. His victory is to finally come forward with his creation, not caring what anyone thinks and not looking for awards. It is easy to nitpick and criticize Coppola's recent independent work for their flaws, whether here in Tetro and in 2007's Youth Without Youth, about an old man who becomes young again, much like the director’s new method. But the flaws in these two films are different from the flaws in his previous features. He just doesn't seem to care, and if he falters it is because he is playing with the reckless passion of a man who understands that he is running out of time.

Artists are very selfish, egotistical people, sublimating their overactive psychology onto a world full of people who cannot ever fully understand them. And so the artist continues again and again, the true meaning of his words hidden between the lines and layers. He wants to reveal the bile of his existence, but must mask it poetically, in effect keeping everyone – including himself – safe. They are jealous of their thoughts which they desire to have seen and touched, but must refrain at the last moment, pulling them away, hiding again in the lukewarm safety of artifice. The boundaries and costumes of civilization are there for a purpose, and what an uninhabitable world it would be if we all took off our well-groomed visages and openly expressed ourselves. Poetry slams tell us this (I guess blogs do too…), and some Friday night "beat" coffeehouses make sessions of artistic expression full-bodied red-faced cringe exhibitions.

Artists are very selfish, egotistical people, sublimating their overactive psychology onto a world full of people who cannot ever fully understand them. And so the artist continues again and again, the true meaning of his words hidden between the lines and layers. He wants to reveal the bile of his existence, but must mask it poetically, in effect keeping everyone – including himself – safe. They are jealous of their thoughts which they desire to have seen and touched, but must refrain at the last moment, pulling them away, hiding again in the lukewarm safety of artifice. The boundaries and costumes of civilization are there for a purpose, and what an uninhabitable world it would be if we all took off our well-groomed visages and openly expressed ourselves. Poetry slams tell us this (I guess blogs do too…), and some Friday night "beat" coffeehouses make sessions of artistic expression full-bodied red-faced cringe exhibitions.

Yet what the hypothetical artist / neurotic displays is not unique to his own nature. The mind is mysterious, and our dark places are more universal than we’d care to acknowledge. With Blue Velvet in 1986, many therapists who viewed the picture believed that David Lynch had to have been sexually traumatized as a child – which he wasn't, at least in the sense that we commonly define sexual trauma; he hadn't even read anything dealing explicitly with psychoanalysis. The brutal truth of Blue Velvet is that it's a vision that encompasses universal psychosexual problems that plague us unconsciously. All men and women have a Frank Booth and Dorothy Vallens in them somewhere, just as they have a Jeffrey Beaumont and Sandy Williams (or even the enigmatic Dean Stockwell character, Ben). Lynch simply dug these images and feelings up within himself and had the bravery to put them on display.

I wonder if I would admire Tetro so much if I was not as aware of the director's own past and relationships. Coppola was the subject of the first film biography I ever read (Peter Cowie's Coppola, first published in 1990, then revised for paperback in 1994), in addition to being the main focus of the first film documentaries I watched in the early 1990s (The Godfather Family and the excellent Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse), and finally he would be the first director that I would analytically study. He was the topic of an eighth grade biography presentation for my English class, and the following summer I would be introduced to serious film criticism by reading about Coppola in Robert Kolker's first edition of A Cinema of Loneliness (the subsequent editions of Kolker's book, published in 1988 and 2000, dropped Coppola from the study, claiming that he'd lost his creativity in the late 1970s; Kolker’s book is my bible of sorts, but he’s wrong). Coppola wears his family life on his sleeve, and to watch his films is to become involved in his personal life, something never more – either genuinely or ironically – felt than in the casting of his daughter Sofia as Michael Corleone's doomed daughter Mary in The Godfather Part III. Given the abusive treatment that the press gave Sofia in the film's aftermath, whether merited or not, it is hard not to hear Mary's dying words – "Dad?" – with a grave significance, directed beyond Michael Corleone and to the real-life director/father, Francis Ford Coppola. As the filmmaker puts it, "They shot at Sofia, when they really wanted to get me." Coppola, like Michael, felt responsible for this assassination. It's the robust emotionalism that Coppola puts in a public statement like that – as found on Godfather III's invaluable DVD commentary – that is the whole sentiment, issued poetically, of Tetro. And that is uncomfortable to watch. From a smug cocktail party perspective, Tetro is pretentious family melodrama. From another, it is an incredibly moving and beautifully rendered confession showcasing the artist's naked soul.

I wonder if I would admire Tetro so much if I was not as aware of the director's own past and relationships. Coppola was the subject of the first film biography I ever read (Peter Cowie's Coppola, first published in 1990, then revised for paperback in 1994), in addition to being the main focus of the first film documentaries I watched in the early 1990s (The Godfather Family and the excellent Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse), and finally he would be the first director that I would analytically study. He was the topic of an eighth grade biography presentation for my English class, and the following summer I would be introduced to serious film criticism by reading about Coppola in Robert Kolker's first edition of A Cinema of Loneliness (the subsequent editions of Kolker's book, published in 1988 and 2000, dropped Coppola from the study, claiming that he'd lost his creativity in the late 1970s; Kolker’s book is my bible of sorts, but he’s wrong). Coppola wears his family life on his sleeve, and to watch his films is to become involved in his personal life, something never more – either genuinely or ironically – felt than in the casting of his daughter Sofia as Michael Corleone's doomed daughter Mary in The Godfather Part III. Given the abusive treatment that the press gave Sofia in the film's aftermath, whether merited or not, it is hard not to hear Mary's dying words – "Dad?" – with a grave significance, directed beyond Michael Corleone and to the real-life director/father, Francis Ford Coppola. As the filmmaker puts it, "They shot at Sofia, when they really wanted to get me." Coppola, like Michael, felt responsible for this assassination. It's the robust emotionalism that Coppola puts in a public statement like that – as found on Godfather III's invaluable DVD commentary – that is the whole sentiment, issued poetically, of Tetro. And that is uncomfortable to watch. From a smug cocktail party perspective, Tetro is pretentious family melodrama. From another, it is an incredibly moving and beautifully rendered confession showcasing the artist's naked soul.

Because Coppola's career has been so erratic, with periods of for-hire work while he tried to build a financial base for constructing his personal films, it is easy to agree with Robert Kolker and see little interpretive value in Coppola as we may find in Scorsese, Altman, or Kubrick. But given the abundance of biographical data available, we can see the personal concerns of the director throughout his body of work. The dynamics of Family, particularly conflicts between brothers, have always been pertinent to Coppola's films, beginning with his first feature Dementia 13 (1963), a Roger Corman-produced horror film set in Ireland involving brothers vying for the inheritance of a family estate (with the imagery of an axe, which ties it neatly to Tetro’s climax). The subsequent films of his early career feature characters who are trapped by the bonds of family and seek to escape from it: You're a Big Boy Now (1966), where the young virgin protagonist is trying to thrive independently and "grow up" apart from his father and doting mother; the light-hearted studio job Finian’s Rainbow (1967) has a daughter moving on from her father; The Rain People (1969), follows a young married woman who inexplicably flees from the responsibilities of a stable marriage; and of course The Godfather, where Michael Corleone insists that he is separate from the illegal and immoral business dealings of his father and the rest of his family. Though an acquired for-hire project, The Godfather documents the key tragic paradox in many Coppola films: one must retain a link to family in order to be "a real man," while at the same time, to be nothing but loyal to family is self-destructive, as Michael's vow to "be with" his father results in the imperilment of his soul. At the conclusion of The Godfather, by ordering the death of his brother-in-law Carlo, and more dramatically in The Godfather Part II, when he orders the death of his biological brother Fredo, Michael is destroying his family by acting to protect it.

Because Coppola's career has been so erratic, with periods of for-hire work while he tried to build a financial base for constructing his personal films, it is easy to agree with Robert Kolker and see little interpretive value in Coppola as we may find in Scorsese, Altman, or Kubrick. But given the abundance of biographical data available, we can see the personal concerns of the director throughout his body of work. The dynamics of Family, particularly conflicts between brothers, have always been pertinent to Coppola's films, beginning with his first feature Dementia 13 (1963), a Roger Corman-produced horror film set in Ireland involving brothers vying for the inheritance of a family estate (with the imagery of an axe, which ties it neatly to Tetro’s climax). The subsequent films of his early career feature characters who are trapped by the bonds of family and seek to escape from it: You're a Big Boy Now (1966), where the young virgin protagonist is trying to thrive independently and "grow up" apart from his father and doting mother; the light-hearted studio job Finian’s Rainbow (1967) has a daughter moving on from her father; The Rain People (1969), follows a young married woman who inexplicably flees from the responsibilities of a stable marriage; and of course The Godfather, where Michael Corleone insists that he is separate from the illegal and immoral business dealings of his father and the rest of his family. Though an acquired for-hire project, The Godfather documents the key tragic paradox in many Coppola films: one must retain a link to family in order to be "a real man," while at the same time, to be nothing but loyal to family is self-destructive, as Michael's vow to "be with" his father results in the imperilment of his soul. At the conclusion of The Godfather, by ordering the death of his brother-in-law Carlo, and more dramatically in The Godfather Part II, when he orders the death of his biological brother Fredo, Michael is destroying his family by acting to protect it.

It is in Godfather II where Coppola's most personal traumas emerge, though he is safely hidden by the period and source material. The relationship between the two surviving Corleone brothers, Michael (Al Pacino) and Fredo (John Cazale), is very poignant. One is powerful, the other is weak. One is feared, the other is vulnerable. One is malevolently silent, while the other speaks too much and is too loud. One seems content, while the other lusts for the power denied him. Overlooking their painful conflict is the memory and insurmountable power of their absent father, Vito (Marlon Brando in the first film; Robert De Niro in Godfather II), a haunting ghost for both sons unable to grasp his calm and grace. These concerns follow Coppola through the 1980s, particularly with both S.E. Hinton adaptations, The Outsiders (1983) and Rumble Fish (1983), The Cotton Club (1985), and of course in the ever-present echoes of Godfather III (1990).

It is in Godfather II where Coppola's most personal traumas emerge, though he is safely hidden by the period and source material. The relationship between the two surviving Corleone brothers, Michael (Al Pacino) and Fredo (John Cazale), is very poignant. One is powerful, the other is weak. One is feared, the other is vulnerable. One is malevolently silent, while the other speaks too much and is too loud. One seems content, while the other lusts for the power denied him. Overlooking their painful conflict is the memory and insurmountable power of their absent father, Vito (Marlon Brando in the first film; Robert De Niro in Godfather II), a haunting ghost for both sons unable to grasp his calm and grace. These concerns follow Coppola through the 1980s, particularly with both S.E. Hinton adaptations, The Outsiders (1983) and Rumble Fish (1983), The Cotton Club (1985), and of course in the ever-present echoes of Godfather III (1990).

Coppola's biography has similarities to the family men in his fiction. He adored his older brother August, who excelled in school, was extremely well-read, and was successful with girls. Young Francis was dopey and suffered from polio which kept him bed-ridden for a long time. He would keep himself company by creating puppet shows. Francis was a mediocre student, had bad skin, and did not read an entire novel until he was fourteen. And yet he wanted to be famous; he wrote his mother, Italia, a letter when he was nine: "Dear Mom – I want to be rich and famous one day. I'm scared that it will not happen." Both brothers were nomadically living in a restless household, the patriarch Carmine moving across the country in search of conducting gigs, obsessed with achieving fame and notoriety. And this father figure too had a brother, also a conductor (Anton Coppola), with whom he was destructively competitive to the point that they became estranged and refused to speak.

Coppola's biography has similarities to the family men in his fiction. He adored his older brother August, who excelled in school, was extremely well-read, and was successful with girls. Young Francis was dopey and suffered from polio which kept him bed-ridden for a long time. He would keep himself company by creating puppet shows. Francis was a mediocre student, had bad skin, and did not read an entire novel until he was fourteen. And yet he wanted to be famous; he wrote his mother, Italia, a letter when he was nine: "Dear Mom – I want to be rich and famous one day. I'm scared that it will not happen." Both brothers were nomadically living in a restless household, the patriarch Carmine moving across the country in search of conducting gigs, obsessed with achieving fame and notoriety. And this father figure too had a brother, also a conductor (Anton Coppola), with whom he was destructively competitive to the point that they became estranged and refused to speak.

The Coppola family drama continued to unfurl as young Francis became the famous celebrity director of the 1970s, while August taught literature and philosophy as a university professor; the sister, Talia, achieved her own notoriety as an actress, first by acting for her brother as Connie Corleone in The Godfather, then becoming Rocky Balboa's wife Adrian in the Rocky films. Francis himself married a WASP (like Michael Corleone with Kay Adams), Eleanor, and had three children – Gian-Carlo, Roman, and Sofia – and established an estate in Napa Valley with a vineyard, seeking to become a new kind of film mogul working out of San Francisco with his company, American Zoetrope. In the late 1970s while working in the jungle on Apocalypse Now, Francis's marriage to Eleanor became strained and it almost ended as he began a relationship with an assistant (these feelings of fidelity he would explore in his next film, the infamous One from the Heart, which was to be connected to his planned four-film adaptation of Goethe's 1809 novel Elective Affinities). The problems of the marriage were documented in Eleanor's memoirs of the period, Notes, published in the early 1980s, while Francis' creative and administrative insecurities were captured by her documentary footage that would serve as a major tool in George Hickenlooper's Hearts of Darkness documentary – much to the apparent disdain of Francis (who has dubbed the film, "Watch Francis Suffer"). The decade saw Francis' financial collapse, losing his studio and latitude while becoming heavily in debt as he had to take on impersonal projects like The Cotton Club (1985). Working as a journeyman, he groomed all three of his children to follow in his footsteps, particularly Gian-Carlo, who directed full musical set-pieces in Cotton Club. This came to a dramatic halt when Gian-Carlo, himself a new father, died in a boating accident in 1987. Meanwhile, August's son Nicolas changed his last name to "Cage" before getting his own career started in his uncle's films Rumble Fish, Cotton Club, and Peggy Sue Got Married. Though he looks a Coppola in every respect, there was a schism that came between father August and son Nicolas when August's wife, the dancer Joy Vogelsang, revealed that she had an affair early in the marriage and that Nicolas may not be August's biological son. Peaks and valleys continued in the 1990s, as The Godfather Part III disappointed many and made Sofia infamous; nominated for the Academy Award of Best Song, Carmine Coppola would have a stroke and die on the very night of the Oscars because he was so agitated that he lost the award to a song performed by Madonna. Dracula's surprising box office success in 1992 saved Francis Coppola and the dreams of Zoetrope, while his winery and tourism businesses in South America became highly profitable. Nicolas Cage won an Academy Award for Leaving Las Vegas, and divided his time between popular Hollywood projects and more eccentric films.

The Coppola family drama continued to unfurl as young Francis became the famous celebrity director of the 1970s, while August taught literature and philosophy as a university professor; the sister, Talia, achieved her own notoriety as an actress, first by acting for her brother as Connie Corleone in The Godfather, then becoming Rocky Balboa's wife Adrian in the Rocky films. Francis himself married a WASP (like Michael Corleone with Kay Adams), Eleanor, and had three children – Gian-Carlo, Roman, and Sofia – and established an estate in Napa Valley with a vineyard, seeking to become a new kind of film mogul working out of San Francisco with his company, American Zoetrope. In the late 1970s while working in the jungle on Apocalypse Now, Francis's marriage to Eleanor became strained and it almost ended as he began a relationship with an assistant (these feelings of fidelity he would explore in his next film, the infamous One from the Heart, which was to be connected to his planned four-film adaptation of Goethe's 1809 novel Elective Affinities). The problems of the marriage were documented in Eleanor's memoirs of the period, Notes, published in the early 1980s, while Francis' creative and administrative insecurities were captured by her documentary footage that would serve as a major tool in George Hickenlooper's Hearts of Darkness documentary – much to the apparent disdain of Francis (who has dubbed the film, "Watch Francis Suffer"). The decade saw Francis' financial collapse, losing his studio and latitude while becoming heavily in debt as he had to take on impersonal projects like The Cotton Club (1985). Working as a journeyman, he groomed all three of his children to follow in his footsteps, particularly Gian-Carlo, who directed full musical set-pieces in Cotton Club. This came to a dramatic halt when Gian-Carlo, himself a new father, died in a boating accident in 1987. Meanwhile, August's son Nicolas changed his last name to "Cage" before getting his own career started in his uncle's films Rumble Fish, Cotton Club, and Peggy Sue Got Married. Though he looks a Coppola in every respect, there was a schism that came between father August and son Nicolas when August's wife, the dancer Joy Vogelsang, revealed that she had an affair early in the marriage and that Nicolas may not be August's biological son. Peaks and valleys continued in the 1990s, as The Godfather Part III disappointed many and made Sofia infamous; nominated for the Academy Award of Best Song, Carmine Coppola would have a stroke and die on the very night of the Oscars because he was so agitated that he lost the award to a song performed by Madonna. Dracula's surprising box office success in 1992 saved Francis Coppola and the dreams of Zoetrope, while his winery and tourism businesses in South America became highly profitable. Nicolas Cage won an Academy Award for Leaving Las Vegas, and divided his time between popular Hollywood projects and more eccentric films.  Finally, Sofia Coppola would culturally redeem herself by directing three brilliant films (The Virgin Suicides, the masterpiece Lost in Translation, and the under-appreciated Marie Antoinette), herself winning an Academy Award for screenwriting. Perhaps inspired by his daughter, Francis quit trying to become a mogul who would finance thoughtful films on a grand scale (which was to be paid for by a controversial $80 million lawsuit Coppola brought against Warner Bros after the studio derailed his heartfelt production of Pinocchio, which was to be dedicated to his dead son), and returned to his pre-Godfather roots, financing modest and personal works with funds from his wine business. The results are mixed (Youth Without Youth, a beautiful experiment, was widely panned) and triumphant (Tetro). Francis Coppola the director is like Tetro the character. They are prodigies of a movement who have estranged themselves from their origins, finally returning to where they had for so long been running; youth without youth indeed.

Finally, Sofia Coppola would culturally redeem herself by directing three brilliant films (The Virgin Suicides, the masterpiece Lost in Translation, and the under-appreciated Marie Antoinette), herself winning an Academy Award for screenwriting. Perhaps inspired by his daughter, Francis quit trying to become a mogul who would finance thoughtful films on a grand scale (which was to be paid for by a controversial $80 million lawsuit Coppola brought against Warner Bros after the studio derailed his heartfelt production of Pinocchio, which was to be dedicated to his dead son), and returned to his pre-Godfather roots, financing modest and personal works with funds from his wine business. The results are mixed (Youth Without Youth, a beautiful experiment, was widely panned) and triumphant (Tetro). Francis Coppola the director is like Tetro the character. They are prodigies of a movement who have estranged themselves from their origins, finally returning to where they had for so long been running; youth without youth indeed.

*

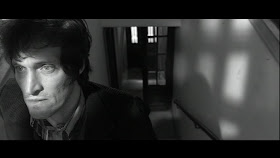

Tetro begins with images of a moth's entrancement with light, trying to assimilate with that bulb and lose itself. The image is intercut with a theatrical spotlight and the face of Tetro, whose actual name is Angelo Tetrocinni. The name is a weird portent for this personality, "tetro" being the Italian word for "gloomy," and as we observe this character early on – alone in his dark room, not wanting to be bothered, locking the whole world out just as he tries to lock himself out of the grips of his past and family – it becomes kind of a humorous tongue-in-cheek commentary (and is why Vincent Gallo is perfect).

Tetro begins with images of a moth's entrancement with light, trying to assimilate with that bulb and lose itself. The image is intercut with a theatrical spotlight and the face of Tetro, whose actual name is Angelo Tetrocinni. The name is a weird portent for this personality, "tetro" being the Italian word for "gloomy," and as we observe this character early on – alone in his dark room, not wanting to be bothered, locking the whole world out just as he tries to lock himself out of the grips of his past and family – it becomes kind of a humorous tongue-in-cheek commentary (and is why Vincent Gallo is perfect).

We follow the younger brother of Tetro, Bennie (Adam Ehrenrich), who appears to be a naval officer but is really just a waiter for a docked cruise ship. He walks the lonely streets of Buenos Aires at night, searching for his brother's apartment, passing by a wavering sign that reads "Wind Sweeps the Road: You Can Not Go Back." Reaching his destination, he is greeted warmly and enthusiastically by Tetro's live-in girlfriend, clueless of his distinguished origins, Miranda (Mirabel Verdu), who admits that Tetro is not really interested in anything from the past.

We follow the younger brother of Tetro, Bennie (Adam Ehrenrich), who appears to be a naval officer but is really just a waiter for a docked cruise ship. He walks the lonely streets of Buenos Aires at night, searching for his brother's apartment, passing by a wavering sign that reads "Wind Sweeps the Road: You Can Not Go Back." Reaching his destination, he is greeted warmly and enthusiastically by Tetro's live-in girlfriend, clueless of his distinguished origins, Miranda (Mirabel Verdu), who admits that Tetro is not really interested in anything from the past.  As Bennie prepares to sleep on the apartment couch, he takes out a letter that Tetro (or Angelo, as the letter is signed) wrote just when he left New York, which ends with the promise that Angie will come back to get Bennie so that they can have adventures together. Of course, this never came to be. Bennie weeps over the letter. His dreams were lost over the course of Angelo's absence as a brother and role model.

As Bennie prepares to sleep on the apartment couch, he takes out a letter that Tetro (or Angelo, as the letter is signed) wrote just when he left New York, which ends with the promise that Angie will come back to get Bennie so that they can have adventures together. Of course, this never came to be. Bennie weeps over the letter. His dreams were lost over the course of Angelo's absence as a brother and role model.

We meet Tetro the next morning. Though warm to Bennie, he is not at all fraternal. He wants to control the conversation and the questions that can be asked, so that the dialogue is not natural and real, but amiably complacent and safely distant ("Who wants a conversation?" he says dismissively). He avoids the realities of his absence, the fact that he has given up the family name, the truth of the imposing father (a famed composer, Carlo Tetroccini, played by Klaus Maria Brandauer), and the thing that Bennie finds most troubling, that Angelo left New York to begin a sabbatical on which he would try to develop as a writer, while then not continuing to write or publish anything, instead being content to lay around and work for the local theatre run by his friend Jose (Rodrigo De la Sirna) as a lighting technician, his own words, thoughts, emotions, etc – all of which are based on an actual historical existence – being bypassed in lieu of safely playing a professional who works for other peoples' creative fantasies, particularly the homosexual performer/playwright Abelardo (Mike Amigorena).

We meet Tetro the next morning. Though warm to Bennie, he is not at all fraternal. He wants to control the conversation and the questions that can be asked, so that the dialogue is not natural and real, but amiably complacent and safely distant ("Who wants a conversation?" he says dismissively). He avoids the realities of his absence, the fact that he has given up the family name, the truth of the imposing father (a famed composer, Carlo Tetroccini, played by Klaus Maria Brandauer), and the thing that Bennie finds most troubling, that Angelo left New York to begin a sabbatical on which he would try to develop as a writer, while then not continuing to write or publish anything, instead being content to lay around and work for the local theatre run by his friend Jose (Rodrigo De la Sirna) as a lighting technician, his own words, thoughts, emotions, etc – all of which are based on an actual historical existence – being bypassed in lieu of safely playing a professional who works for other peoples' creative fantasies, particularly the homosexual performer/playwright Abelardo (Mike Amigorena).

Bennie is introduced to Tetro's hip artist friends, but not as a brother – he's just a friend. This makes Bennie, who has adoring memories of his brother, angry. Without a family context in this relationship with Tetro, he is nothing but a bit player, an unnecessary add-on in the still-life drama of a mysterious man's existence that is heading nowhere. "Why don't you introduce me as your brother?" he asks Tetro, who responds by reminding Bennie that the younger brother is not allowed to ask such intrusive questions. Tetro has completely closed himself off from links to history. His passion is closing off his outlet for expressing passion, and that passion is rooted in the trauma of the early domestic experiences involving his relationship to his father, Carlo. Curious to learn about his enigmatic brother, Bennie snoops throughout the apartment and discovers Tetro's unfinished play. It is essentially a document detailing his relationship to the father, the dramatic loss of his soprano mother (killed in a car crash while Tetro/Angelo was driving), and his ambition to be a great artist.

Bennie is introduced to Tetro's hip artist friends, but not as a brother – he's just a friend. This makes Bennie, who has adoring memories of his brother, angry. Without a family context in this relationship with Tetro, he is nothing but a bit player, an unnecessary add-on in the still-life drama of a mysterious man's existence that is heading nowhere. "Why don't you introduce me as your brother?" he asks Tetro, who responds by reminding Bennie that the younger brother is not allowed to ask such intrusive questions. Tetro has completely closed himself off from links to history. His passion is closing off his outlet for expressing passion, and that passion is rooted in the trauma of the early domestic experiences involving his relationship to his father, Carlo. Curious to learn about his enigmatic brother, Bennie snoops throughout the apartment and discovers Tetro's unfinished play. It is essentially a document detailing his relationship to the father, the dramatic loss of his soprano mother (killed in a car crash while Tetro/Angelo was driving), and his ambition to be a great artist.

In contrast to the static black and white compositions of the present story, Tetro's scripting of the past is filmed in hand-held saturated vibrant color. Carlo Tetroccini learns that his son Angelo wants to be a great writer – and a genius, no less. "There can only be one genius in a family," the father tells the son, as if the pearls of great artistry will not be shared. Earlier, we saw Carlo suggest to his own brother Alfie (also played by Klaus Maria Brandauer) that he change his last name, even though Alfie is older. What we see of the father is a something of a compassionate man, nevertheless too egocentric to share his family's legacy with anyone else. This is cruelly evident when young Tetro brings home a dancer girlfriend, whom Carlo amuses with his piano playing, and then ultimately will seduce (a blatant parallel to the question of the fidelity of August’s wife, who was a dancer).

In contrast to the static black and white compositions of the present story, Tetro's scripting of the past is filmed in hand-held saturated vibrant color. Carlo Tetroccini learns that his son Angelo wants to be a great writer – and a genius, no less. "There can only be one genius in a family," the father tells the son, as if the pearls of great artistry will not be shared. Earlier, we saw Carlo suggest to his own brother Alfie (also played by Klaus Maria Brandauer) that he change his last name, even though Alfie is older. What we see of the father is a something of a compassionate man, nevertheless too egocentric to share his family's legacy with anyone else. This is cruelly evident when young Tetro brings home a dancer girlfriend, whom Carlo amuses with his piano playing, and then ultimately will seduce (a blatant parallel to the question of the fidelity of August’s wife, who was a dancer).

What are the father's motivations? Is it revenge, as Angelo was responsible for the mother's death? Or, even more troubling, is it because the powerful individual is seducing his son's girlfriend simply because he can? Tetro seems to believe that it's this latter reason. The sordid love triangle is expressed by Coppola in a third form of presenting his film: beautifully colorized ballet sequences that evoke the Powell and Pressburger films of the 1940s, in particular Tales of Hoffman and The Red Shoes. The girlfriend herself is presented as a manifestation of Angelo's own fears of women and love, being that the organically conventional love relationship she shares with him is replaced by her becoming a clock-work machine prone to manipulation, easily controlled by power of the wand-waving conductor-father who monopolizes his power and genius.

What are the father's motivations? Is it revenge, as Angelo was responsible for the mother's death? Or, even more troubling, is it because the powerful individual is seducing his son's girlfriend simply because he can? Tetro seems to believe that it's this latter reason. The sordid love triangle is expressed by Coppola in a third form of presenting his film: beautifully colorized ballet sequences that evoke the Powell and Pressburger films of the 1940s, in particular Tales of Hoffman and The Red Shoes. The girlfriend herself is presented as a manifestation of Angelo's own fears of women and love, being that the organically conventional love relationship she shares with him is replaced by her becoming a clock-work machine prone to manipulation, easily controlled by power of the wand-waving conductor-father who monopolizes his power and genius.

This kind of sacrilegious attitude towards family, where the whole group is personified in the shape of a single figurehead instead of a community of members, extends to the mystery of Tetro's relationship to Bennie. It becomes evident to us that Angelo's former girlfriend is in fact Bennie's mother, and Carlo's next wife. This is why Bennie becomes obsessed with Tetro's unfinished and cryptic play. It is not just Tetro/Angie's story, but Bennie's. The family's tumultuous past belongs to both of them. Bennie copies and finishes Tetro's play, which was written in "military school code," requiring a mirror to be read and copied and continuing Coppola's motif of reflection.

This kind of sacrilegious attitude towards family, where the whole group is personified in the shape of a single figurehead instead of a community of members, extends to the mystery of Tetro's relationship to Bennie. It becomes evident to us that Angelo's former girlfriend is in fact Bennie's mother, and Carlo's next wife. This is why Bennie becomes obsessed with Tetro's unfinished and cryptic play. It is not just Tetro/Angie's story, but Bennie's. The family's tumultuous past belongs to both of them. Bennie copies and finishes Tetro's play, which was written in "military school code," requiring a mirror to be read and copied and continuing Coppola's motif of reflection.

Bennie discovers more about his brother while watching a theatrical production of Fausta, a female version of the Faust story. Midway through the performance, Tetro begins taunting the writer/star Abelardo for how ludicrous the story is, obviously sublimating his own lack of creative output on a mediocre, though successful, artist who is able to do precisely what Tetro doesn't allow himself to do. Tetro's humorous interruption is broken by the arrival of a dark and distinguished looking middle-aged woman whom the artists all venerate: a great critic and writer, known by the pseudonym "Alone." Alone was Tetro's mentor until the two had a falling-out, resulting in Tetro abandonment of writing altogether. She asks the performers to continue with Fausta, which has become a highly sexual peep-show as the aged Fausta has been made young and begins to strip. The insinuation here is that the performer or artist is an exhibitionist, baring herself for the amusement and stimulation of others; this stands in contrast to the disposition of in-the-dark Tetro, who has killed his real identity: "Angelo is dead," he says to Bennie, adding that no one in Buenos Aires knows that he is the son of the famous conductor Carlo Tetroccini; much like with Stephen Dedalus in Joyce's Ulysses, history is a nightmare for Tetro.

Bennie discovers more about his brother while watching a theatrical production of Fausta, a female version of the Faust story. Midway through the performance, Tetro begins taunting the writer/star Abelardo for how ludicrous the story is, obviously sublimating his own lack of creative output on a mediocre, though successful, artist who is able to do precisely what Tetro doesn't allow himself to do. Tetro's humorous interruption is broken by the arrival of a dark and distinguished looking middle-aged woman whom the artists all venerate: a great critic and writer, known by the pseudonym "Alone." Alone was Tetro's mentor until the two had a falling-out, resulting in Tetro abandonment of writing altogether. She asks the performers to continue with Fausta, which has become a highly sexual peep-show as the aged Fausta has been made young and begins to strip. The insinuation here is that the performer or artist is an exhibitionist, baring herself for the amusement and stimulation of others; this stands in contrast to the disposition of in-the-dark Tetro, who has killed his real identity: "Angelo is dead," he says to Bennie, adding that no one in Buenos Aires knows that he is the son of the famous conductor Carlo Tetroccini; much like with Stephen Dedalus in Joyce's Ulysses, history is a nightmare for Tetro.

News comes from New York that Carlo has had a stroke and is dying; he wants both of his sons by his bedside in his final hours. This is a confrontation that is unbearable for Tetro. To confront the past while making peace with it is just as troubling as facing the future, where one resides in non-being. It is very comfortable for Tetro to abide in his static existence of simply being a hack technician, rather than expose himself in front of his peers and be made vulnerable.

News comes from New York that Carlo has had a stroke and is dying; he wants both of his sons by his bedside in his final hours. This is a confrontation that is unbearable for Tetro. To confront the past while making peace with it is just as troubling as facing the future, where one resides in non-being. It is very comfortable for Tetro to abide in his static existence of simply being a hack technician, rather than expose himself in front of his peers and be made vulnerable.

Tetro has warmed up to Bennie – slightly. After Bennie is injured in a motorcycle collision, Tetro visits Bennie in the hospital, bearing flowers. However, Tetro discovers what Bennie is doing with the unfinished play, which makes the older brother ferociously angry. The play is Tetro's "life," and belongs solely to him, and being that the life that it portrays is of someone who is no more ("Angelo") it is not meant to be seen by anyone. Bennie retorts that it's "his life too," and therefore it belongs to both of them. Strangely, Tetro doesn't take the manuscript back as he leaves the hospital room in a fiery rush. Deep down, he wants to story to be finished. The outcome is apparently successful, being that Alone has read the finished manuscript and has selected it to be presented as one of the finalists in a theatrical competition where the brothers and performers will be surrounded by the press and famed dignitaries of the arts.

Tetro has warmed up to Bennie – slightly. After Bennie is injured in a motorcycle collision, Tetro visits Bennie in the hospital, bearing flowers. However, Tetro discovers what Bennie is doing with the unfinished play, which makes the older brother ferociously angry. The play is Tetro's "life," and belongs solely to him, and being that the life that it portrays is of someone who is no more ("Angelo") it is not meant to be seen by anyone. Bennie retorts that it's "his life too," and therefore it belongs to both of them. Strangely, Tetro doesn't take the manuscript back as he leaves the hospital room in a fiery rush. Deep down, he wants to story to be finished. The outcome is apparently successful, being that Alone has read the finished manuscript and has selected it to be presented as one of the finalists in a theatrical competition where the brothers and performers will be surrounded by the press and famed dignitaries of the arts.

The journey to the competition becomes a ritual of maturity for Bennie, who finds himself deflowered in a threesome with one of the play's actresses and her niece. Tetro understands what is happening to Bennie, and mysteriously disappears, bothered. Just earlier, as the group was driving past the icy mountains, Tetro found himself disappearing in the sparkling light of the sun reflecting off of the ice, much like the moth entering the flame at the film's beginning. This period, added with the weight of understanding his father's mortality, is bidding him to undergo a change and unveiling of his own new maturity. But is he suicidal? When Tetro disappears from the resort where the group is staying, Miranda and Bennie are alarmed by a car crashing. They (and the audience) are convinced that Tetro (whom has walked in front of buses before) has volitionally collided with traffic. But it is only a deer. Tetro is gone.

The journey to the competition becomes a ritual of maturity for Bennie, who finds himself deflowered in a threesome with one of the play's actresses and her niece. Tetro understands what is happening to Bennie, and mysteriously disappears, bothered. Just earlier, as the group was driving past the icy mountains, Tetro found himself disappearing in the sparkling light of the sun reflecting off of the ice, much like the moth entering the flame at the film's beginning. This period, added with the weight of understanding his father's mortality, is bidding him to undergo a change and unveiling of his own new maturity. But is he suicidal? When Tetro disappears from the resort where the group is staying, Miranda and Bennie are alarmed by a car crashing. They (and the audience) are convinced that Tetro (whom has walked in front of buses before) has volitionally collided with traffic. But it is only a deer. Tetro is gone.

Bennie and the actors arrive at the theatrical competition, bathed in media light and publicity, the cameras and theatrical pundits toasting all the guests of honor with pleasantries and compliments. It is a fashionable and glitzy world, while at the same time repugnant and artificial, suggesting that this lensed and lit palace of rewards could not be more opposite from the emotions of art that are being produced and performed. In this sequence, the black and white photography added to the paparazzi-textured mise-en-scene evokes the film festival-laden worlds Fellini created in La Dolce Vita and then with a more surreal and psychological bent in 8 ½. It calls into question something that surely must have been on Coppola's mind throughout the moments of honor he received throughout the 1970s, just as surely as it must have struck Fellini: how is it that art, which is so personal, naked, and expressive, becomes aligned with the superficialities of fashion and pop punditry? I've been to a few social soirees where art is exhibited by scene elites dressed in their best as they munch off of expensive catering and champagne. Yet I find such events bizarre in how the topics of discussion are shallow, when maybe there should be deep discourse. It feels mechanical and wafer thin. It's an ironic display of an artificial aristocracy as performed by artists who are anything but starving, serving as a secure blanket that hushes any kind of profound observations or ugly truisms embedded within the art on display.

Bennie and the actors arrive at the theatrical competition, bathed in media light and publicity, the cameras and theatrical pundits toasting all the guests of honor with pleasantries and compliments. It is a fashionable and glitzy world, while at the same time repugnant and artificial, suggesting that this lensed and lit palace of rewards could not be more opposite from the emotions of art that are being produced and performed. In this sequence, the black and white photography added to the paparazzi-textured mise-en-scene evokes the film festival-laden worlds Fellini created in La Dolce Vita and then with a more surreal and psychological bent in 8 ½. It calls into question something that surely must have been on Coppola's mind throughout the moments of honor he received throughout the 1970s, just as surely as it must have struck Fellini: how is it that art, which is so personal, naked, and expressive, becomes aligned with the superficialities of fashion and pop punditry? I've been to a few social soirees where art is exhibited by scene elites dressed in their best as they munch off of expensive catering and champagne. Yet I find such events bizarre in how the topics of discussion are shallow, when maybe there should be deep discourse. It feels mechanical and wafer thin. It's an ironic display of an artificial aristocracy as performed by artists who are anything but starving, serving as a secure blanket that hushes any kind of profound observations or ugly truisms embedded within the art on display.

There is an impression of unpredictability during this climactic part of Tetro, as the ugly truth of an artist's reality must by necessity stand in a kind of opposing posture to the niceties of the gala event. Outside of the building where a sample of the Tetrocinni play is being performed, Tetro confronts Bennie about the truth. "How does the play end?" Tetro asks Bennie, who took it upon himself to finish the work. "The father dies," is Bennie's response. The son kills the father who betrayed and stole the girlfriend. Tetro reveals an axe and offers it to Bennie.

There is an impression of unpredictability during this climactic part of Tetro, as the ugly truth of an artist's reality must by necessity stand in a kind of opposing posture to the niceties of the gala event. Outside of the building where a sample of the Tetrocinni play is being performed, Tetro confronts Bennie about the truth. "How does the play end?" Tetro asks Bennie, who took it upon himself to finish the work. "The father dies," is Bennie's response. The son kills the father who betrayed and stole the girlfriend. Tetro reveals an axe and offers it to Bennie.

The catharsis that Tetro desires for his own life, and that any dramatic work demands, must here be enacted, as it is revealed that Angie is in fact Bennie's father, not Carlo. "You have to kill me," Tetro says, wanting his sibling/son to take the axe and finish it. The proposition of death is much more shocking and frightening than the revelation of the Tetrocinni family secret, given the corporeal nature of such a death and its possibility – the over-the-top exhibitions of artifice inside the festival hall, in fact, demand such a contrasting act of violence. But Bennie, shocked, flees and leaves Tetro, who is soon swarmed by cameras and microphones congratulating him on his creative accomplishment.

The catharsis that Tetro desires for his own life, and that any dramatic work demands, must here be enacted, as it is revealed that Angie is in fact Bennie's father, not Carlo. "You have to kill me," Tetro says, wanting his sibling/son to take the axe and finish it. The proposition of death is much more shocking and frightening than the revelation of the Tetrocinni family secret, given the corporeal nature of such a death and its possibility – the over-the-top exhibitions of artifice inside the festival hall, in fact, demand such a contrasting act of violence. But Bennie, shocked, flees and leaves Tetro, who is soon swarmed by cameras and microphones congratulating him on his creative accomplishment.  Alone, the critic, materializes to bestow on Tetro the coveted award for the evening – but he strangely turns her down. "I don't need your approval anymore," he says, walking away. She, in retaliation, slashes her finger along her throat, signaling an end to the cameras, microphones, and electricity. Tetro, like Coppola with Tetro, is abandoning his hindering self-consciousness and safeguards, devoting himself to the truths of his life and expressions of his mind at the cost of relying on any kind of approval, which haunted him throughout his childhood with his mother and father, and throughout his career as an artist surrounded by critics. Alone's name bespeaks an artist's attitude towards the safe world of critics, being that critics are able to hermetically seal themselves off from the rest of the world and thus from any kind of outside vulnerabilities; they are fashionista insiders. The critic and the artist are thus breeds apart. Tetro must break through his own isolating wall, where he safely criticizes other artists while simultaneously creates nothing but light, the same light that he saw in headlights stealing away his mother’s life, and which have entranced him ever since.

Alone, the critic, materializes to bestow on Tetro the coveted award for the evening – but he strangely turns her down. "I don't need your approval anymore," he says, walking away. She, in retaliation, slashes her finger along her throat, signaling an end to the cameras, microphones, and electricity. Tetro, like Coppola with Tetro, is abandoning his hindering self-consciousness and safeguards, devoting himself to the truths of his life and expressions of his mind at the cost of relying on any kind of approval, which haunted him throughout his childhood with his mother and father, and throughout his career as an artist surrounded by critics. Alone's name bespeaks an artist's attitude towards the safe world of critics, being that critics are able to hermetically seal themselves off from the rest of the world and thus from any kind of outside vulnerabilities; they are fashionista insiders. The critic and the artist are thus breeds apart. Tetro must break through his own isolating wall, where he safely criticizes other artists while simultaneously creates nothing but light, the same light that he saw in headlights stealing away his mother’s life, and which have entranced him ever since.

Carlo Tetrocinni is buried, his legacy sealed in a mask and the passing on of his conductor's wand to the new patriarch, the exiled brother Alfie, who accepts it generously but with mixed feelings being that he never made peace with his brother in life (so was also the case between Carmine and Anton, the dueling Coppola musicians). The funeral is interrupted by Bennie's drunken behavior. To the entire family he exposes his roots and the dangerously megalomaniacal power of Carlo. The dead man, so honored, was never his father after all, and was in fact a traitor to the sanctity of Family.

Carlo Tetrocinni is buried, his legacy sealed in a mask and the passing on of his conductor's wand to the new patriarch, the exiled brother Alfie, who accepts it generously but with mixed feelings being that he never made peace with his brother in life (so was also the case between Carmine and Anton, the dueling Coppola musicians). The funeral is interrupted by Bennie's drunken behavior. To the entire family he exposes his roots and the dangerously megalomaniacal power of Carlo. The dead man, so honored, was never his father after all, and was in fact a traitor to the sanctity of Family.

Bennie leaves the funeral and walks into the dense oncoming traffic, where a flurry of endless lights head towards him. It is Tetro, reborn as Angelo, who comes to his rescue, following his brother/son into the traffic and grabbing him, embracing him and withholding nothing in affection. This steely rock of a gloomy individual, Tetro, then tells Bennie, "Don't look into the light. You have to close your eyes. Just don't look into the light." He affirms his position in the family, as a real individual in the chain of history, saying "You're my son. We're family," and guides Bennie back to safety.

Bennie leaves the funeral and walks into the dense oncoming traffic, where a flurry of endless lights head towards him. It is Tetro, reborn as Angelo, who comes to his rescue, following his brother/son into the traffic and grabbing him, embracing him and withholding nothing in affection. This steely rock of a gloomy individual, Tetro, then tells Bennie, "Don't look into the light. You have to close your eyes. Just don't look into the light." He affirms his position in the family, as a real individual in the chain of history, saying "You're my son. We're family," and guides Bennie back to safety.

It's this moment of final embrace, so beautifully photographed by Mihai Malaimare Jr., which for me sealed Tetro as a powerful experience. As I wrote earlier, Tetro's melodrama and lack of inhibition may easily lead some to deride it as overly self-indulgent and pretentious. Interpreting it is heady work, given that Coppola has layered the picture with such density: motifs of mirrors and light, colors, allusions, and metaphors. Very much rides on the final crescendo where the emotional melody is tightly compacted with an explosive outburst in the final image. Like The Godfather trilogy or Apocalypse Now, Coppola is not interested in realism so much as operatic expressionism where real emotions are poeticized in mythic brush-strokes. The ballets of Tetro are a metaphor for how Coppola works. All of Tetro's melancholy, density of plot and meaning, and unrestrained emotion is here at the finale when Angelo and Bennie are reunited and born again together in the inexplicable closeness of filial blood. The sheer nakedness of the moment mirrors Coppola's frankness as storyteller and confessor. Given the flaws and highly outspoken moments that have warranted this 70-year-old master filmmaker so much criticism and infamy to match and overshadow his evident genius, his sins are forgiven and entire career is affirmed. It seems that the conclusion of Tetro brings Francis Ford Coppola back to his long-abandoned origins and dreams, where for so long we have impatiently waited for his return.

It's this moment of final embrace, so beautifully photographed by Mihai Malaimare Jr., which for me sealed Tetro as a powerful experience. As I wrote earlier, Tetro's melodrama and lack of inhibition may easily lead some to deride it as overly self-indulgent and pretentious. Interpreting it is heady work, given that Coppola has layered the picture with such density: motifs of mirrors and light, colors, allusions, and metaphors. Very much rides on the final crescendo where the emotional melody is tightly compacted with an explosive outburst in the final image. Like The Godfather trilogy or Apocalypse Now, Coppola is not interested in realism so much as operatic expressionism where real emotions are poeticized in mythic brush-strokes. The ballets of Tetro are a metaphor for how Coppola works. All of Tetro's melancholy, density of plot and meaning, and unrestrained emotion is here at the finale when Angelo and Bennie are reunited and born again together in the inexplicable closeness of filial blood. The sheer nakedness of the moment mirrors Coppola's frankness as storyteller and confessor. Given the flaws and highly outspoken moments that have warranted this 70-year-old master filmmaker so much criticism and infamy to match and overshadow his evident genius, his sins are forgiven and entire career is affirmed. It seems that the conclusion of Tetro brings Francis Ford Coppola back to his long-abandoned origins and dreams, where for so long we have impatiently waited for his return.

Not that the melodrama of this film is completely fact. But the story certainly correlates to emotional truisms deeply felt by Francis Ford Coppola, perhaps budded during those long lonely hours as a sickly polio-afflicted youth, dreaming of fame while envying and blindly loving his older brother August, the intellectual ladies' man, both boys living under the eye of a very proud and egotistical father, the composer/conductor Carmine Coppola – who may have been resentful of the eventual notoriety his children achieved. No character in Tetro is necessarily a concrete stand-in for a real-life Coppola; rather they are more possibly amalgamations of a few of them, all of the Coppolas finding multiple faces in the myriad of characters. For example, Tetro (Vincent Gallo), has changed his name, not wanting anything to do with his biological family, something that makes one think of Francis’s nephew, the movie megastar Nicolas Cage. But Tetro is also certainly August, the admired artist held in awe by his younger brother, and is also Francis. Tetro has put his talent on hold, fearful to express what he has written, while in the meantime he works in theatre as a talented lighting-man – a professional hack. Tetro’s insecurity is like Coppola's, who is admitting his frustration with his critics. His victory is to finally come forward with his creation, not caring what anyone thinks and not looking for awards. It is easy to nitpick and criticize Coppola's recent independent work for their flaws, whether here in Tetro and in 2007's Youth Without Youth, about an old man who becomes young again, much like the director’s new method. But the flaws in these two films are different from the flaws in his previous features. He just doesn't seem to care, and if he falters it is because he is playing with the reckless passion of a man who understands that he is running out of time.

Not that the melodrama of this film is completely fact. But the story certainly correlates to emotional truisms deeply felt by Francis Ford Coppola, perhaps budded during those long lonely hours as a sickly polio-afflicted youth, dreaming of fame while envying and blindly loving his older brother August, the intellectual ladies' man, both boys living under the eye of a very proud and egotistical father, the composer/conductor Carmine Coppola – who may have been resentful of the eventual notoriety his children achieved. No character in Tetro is necessarily a concrete stand-in for a real-life Coppola; rather they are more possibly amalgamations of a few of them, all of the Coppolas finding multiple faces in the myriad of characters. For example, Tetro (Vincent Gallo), has changed his name, not wanting anything to do with his biological family, something that makes one think of Francis’s nephew, the movie megastar Nicolas Cage. But Tetro is also certainly August, the admired artist held in awe by his younger brother, and is also Francis. Tetro has put his talent on hold, fearful to express what he has written, while in the meantime he works in theatre as a talented lighting-man – a professional hack. Tetro’s insecurity is like Coppola's, who is admitting his frustration with his critics. His victory is to finally come forward with his creation, not caring what anyone thinks and not looking for awards. It is easy to nitpick and criticize Coppola's recent independent work for their flaws, whether here in Tetro and in 2007's Youth Without Youth, about an old man who becomes young again, much like the director’s new method. But the flaws in these two films are different from the flaws in his previous features. He just doesn't seem to care, and if he falters it is because he is playing with the reckless passion of a man who understands that he is running out of time.

Coppola's biography has similarities to the family men in his fiction. He adored his older brother August, who excelled in school, was extremely well-read, and was successful with girls. Young Francis was dopey and suffered from polio which kept him bed-ridden for a long time. He would keep himself company by creating puppet shows. Francis was a mediocre student, had bad skin, and did not read an entire novel until he was fourteen. And yet he wanted to be famous; he wrote his mother, Italia, a letter when he was nine: "Dear Mom – I want to be rich and famous one day. I'm scared that it will not happen." Both brothers were nomadically living in a restless household, the patriarch Carmine moving across the country in search of conducting gigs, obsessed with achieving fame and notoriety. And this father figure too had a brother, also a conductor (Anton Coppola), with whom he was destructively competitive to the point that they became estranged and refused to speak.

Coppola's biography has similarities to the family men in his fiction. He adored his older brother August, who excelled in school, was extremely well-read, and was successful with girls. Young Francis was dopey and suffered from polio which kept him bed-ridden for a long time. He would keep himself company by creating puppet shows. Francis was a mediocre student, had bad skin, and did not read an entire novel until he was fourteen. And yet he wanted to be famous; he wrote his mother, Italia, a letter when he was nine: "Dear Mom – I want to be rich and famous one day. I'm scared that it will not happen." Both brothers were nomadically living in a restless household, the patriarch Carmine moving across the country in search of conducting gigs, obsessed with achieving fame and notoriety. And this father figure too had a brother, also a conductor (Anton Coppola), with whom he was destructively competitive to the point that they became estranged and refused to speak.

Finally, Sofia Coppola would culturally redeem herself by directing three brilliant films (The Virgin Suicides, the masterpiece Lost in Translation, and the under-appreciated Marie Antoinette), herself winning an Academy Award for screenwriting. Perhaps inspired by his daughter, Francis quit trying to become a mogul who would finance thoughtful films on a grand scale (which was to be paid for by a controversial $80 million lawsuit Coppola brought against Warner Bros after the studio derailed his heartfelt production of Pinocchio, which was to be dedicated to his dead son), and returned to his pre-Godfather roots, financing modest and personal works with funds from his wine business. The results are mixed (Youth Without Youth, a beautiful experiment, was widely panned) and triumphant (Tetro). Francis Coppola the director is like Tetro the character. They are prodigies of a movement who have estranged themselves from their origins, finally returning to where they had for so long been running; youth without youth indeed.

Finally, Sofia Coppola would culturally redeem herself by directing three brilliant films (The Virgin Suicides, the masterpiece Lost in Translation, and the under-appreciated Marie Antoinette), herself winning an Academy Award for screenwriting. Perhaps inspired by his daughter, Francis quit trying to become a mogul who would finance thoughtful films on a grand scale (which was to be paid for by a controversial $80 million lawsuit Coppola brought against Warner Bros after the studio derailed his heartfelt production of Pinocchio, which was to be dedicated to his dead son), and returned to his pre-Godfather roots, financing modest and personal works with funds from his wine business. The results are mixed (Youth Without Youth, a beautiful experiment, was widely panned) and triumphant (Tetro). Francis Coppola the director is like Tetro the character. They are prodigies of a movement who have estranged themselves from their origins, finally returning to where they had for so long been running; youth without youth indeed.

No comments:

Post a Comment